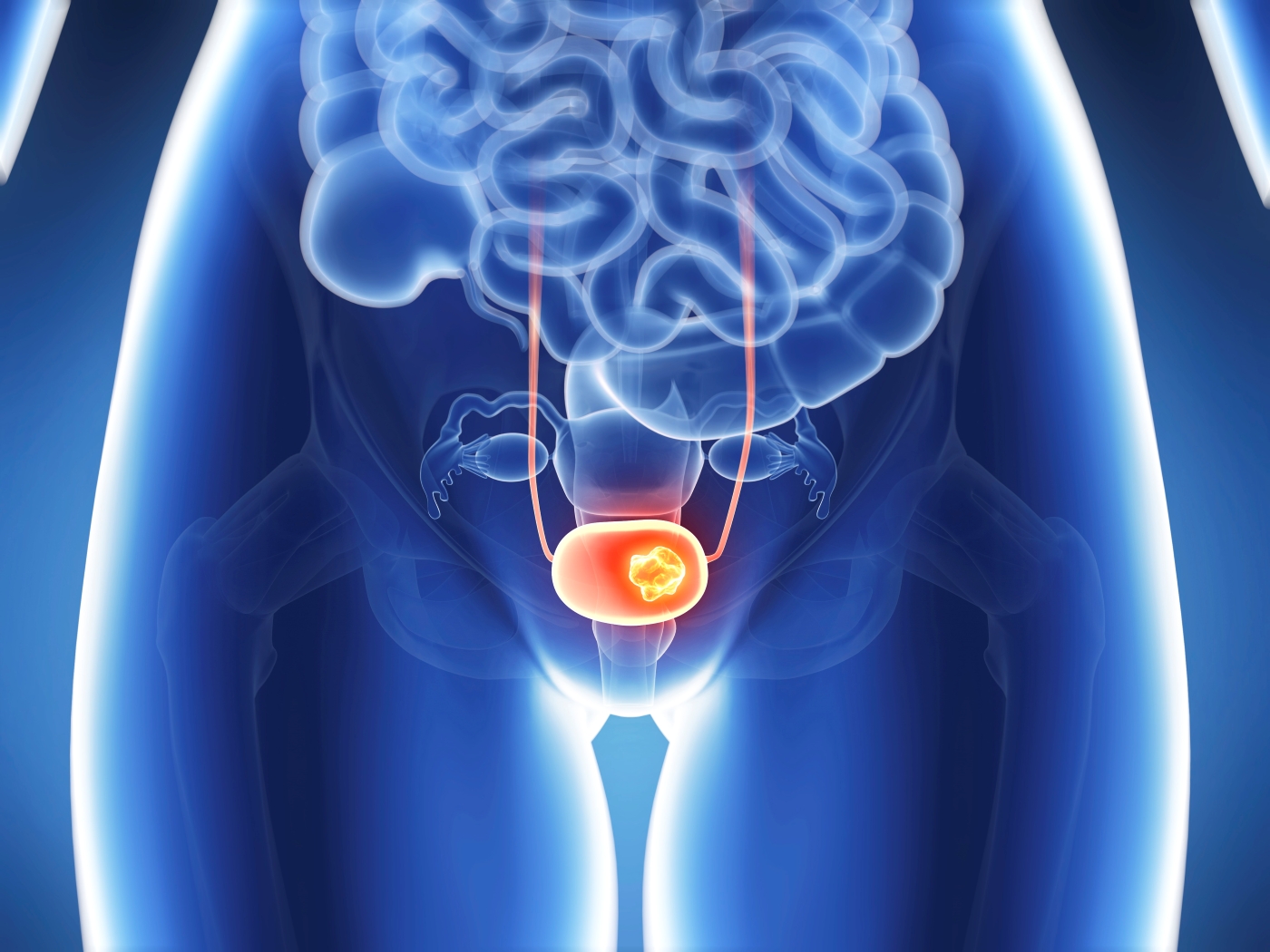

Bladder cancer is the fourth-most common cancer among men and the sixth-most common type overall in the U.S. It’s also one of the most decision-heavy cancers for patients, requiring many personal choices regarding treatment that will affect their future quality of life.

About 75% of bladder cancers are diagnosed before the cancer grows beyond the bladder and into surrounding muscle. Most of these non-muscle invasive bladder cancers can be treated with minimally invasive surgery and medication, keeping the bladder intact and daily life relatively normal.

The other 25% of newly diagnosed patients have the more serious muscle-invasive disease. In addition, some patients with non-muscle invasive disease will progress to muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Effective treatments for this type are limited. This is where the treatment options become more complex, and the decisions made have more impact on future quality of life.

Deion “Coach Prime” Sanders, a Pro Football Hall of Famer and former Dallas Cowboy who now coaches football at the University of Colorado, had one of these aggressive cancers, according to an interview with his doctors on Today. Sanders chose to get a cystectomy, which is a surgery to remove his bladder and prostate and divert his urine. He shared his diagnosis and treatment decisions in a July news conference.

There is no prosthetic device or transplant procedure to replace the bladder. So when the bladder is removed, a new one must be constructed using a portion of the patient’s small intestine. In general, there are three surgical options to do that, all with different impacts on long-term quality of life. Sanders chose an ileal neobladder, which allows him to urinate close to normally during his waking hours.

Cystectomy and bladder reconstruction can be lifesaving, but it is also life-changing. As the only National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center in North Texas, UT Southwestern is a high-volume center for cystectomies and bladder reconstructions. Over half of our patients travel 50 miles or more for the expertise of our urological reconstruction experts.

Every bladder cancer treatment decision should be made with the guidance of a specialist team that understands your type of cancer and the lifestyle considerations that matter most to you. Our experts will support you in making informed treatment decisions, starting from the moment of diagnosis.

How is bladder cancer diagnosed?

When the bladder is healthy, it expands to hold urine until it is full. Then it signals the brain that it's time to urinate and contracts after you go to the bathroom. Cancer disrupts this process. Most people with bladder cancer experience no symptoms. The first sign of a problem is typically blood in the urine, which may appear pink, red, or rust-colored. Some people may also have increased frequency or urgency in urination.

As bladder cancer progresses, it can cause blocked urine flow, painful urination, pelvic and lower back pain, swollen feet, loss of appetite, and kidney problems.

Diagnosis begins with testing a urine sample for blood or cancer cells. A specialist will perform a cystoscopy to examine the inside of the bladder. A thin, lighted flexible scope is guided through the urethra to the bladder, and the technology shows us small, difficult-to-spot cancers early in the disease process.

If we spot a tumor, we will take the patients to the operating room where we will remove the tumor and send the specimen for pathologic testing. If the report confirms cancer, it will also tell us the stage (whether the cancer has spread and how far) and grade:

- High-grade: Fast-growing cancer with very abnormal cells

- Low-grade: Slow-growing cancer with less abnormal cells

A CT scan can help identify signs of growth outside the bladder wall. Our specialist team will meet to discuss the collective findings and design a treatment plan based on the cancer stage and grade and your personal preferences.

What are the treatment options for bladder cancer?

Whenever possible, we recommend starting with bladder-preserving treatments to control the cancer with less impact on your daily life.

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

Most people with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer will not need cystectomy and bladder reconstruction surgery. Patients typically have good outcomes with transurethral resection of the bladder tumor. This incision-free surgery removes the tumor through the urethra, where urine exits the body.

Low-risk tumors are solitary and less than 3 centimeters long. These tumors have a 20%-30% chance of coming back. Three months after surgery, then every 12 months for at least five years, we examine the patient for signs of recurrence. Active monitoring means patients can avoid procedures or medications that may not be needed.

Patients with multiple or recurrent noninvasive tumors are at higher risk for recurrence or progression (when tumor becomes more aggressive). These tumors are treated with medications that are instilled in the bladder using a catheter (intravesical therapies).

There are two different types of medication: immune therapies and chemotherapy.

Intravesical immune therapies (such as Bacille Calmette Guerin, or BCG) are preferred for high-grade cancers while intravesical chemotherapy like gemcitabine is preferred for low-grade cancers.

The good news is that the bladder does not absorb liquids, so treatments given as liquids in the bladder usually stay confined to the bladder. That means most patients do not have significant side effects such as nausea or hair loss that can occur when you get treatments using an IV into the blood stream. Some patients will experience local symptoms such as urinary frequency, urgency, and discomfort, but these symptoms are generally well tolerated.

If none of these options controls the cancer, or in certain cases of non-muscle invasive cancer with a high risk of recurrence, we may recommend cystectomy.

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer

About 25% of bladder cancers are diagnosed after the cancer has spread beyond the lining of the bladder and into its muscle wall. These muscle-invasive cancers require a more intensive treatment approach, which usually involves surgery.

Transurethral tumor resection surgery is typically the first step. Then, depending on how far the cancer extends into the muscle, the treatment plan may include:

- Targeted radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy. Also called tri-modality therapy, this is a bladder-preserving approach offered at only a handful of centers in the U.S., including at UTSW.

- Pre-surgery (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy or immunotherapy, followed by cystectomy to remove all or part of the bladder.

- Chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy after cystectomy.

If you choose cystectomy, there are three general options for the surgery. Each has a different effect on how you will store and dispose of urine for the rest of your life. Talk with your specialist team about your options, and don’t hesitate to seek additional opinions if needed.

UT Southwestern Medical Center is ranked by U.S. News & World Report as one of the nation's top 20 hospitals for cancer care. Our team of hundreds of leading cancer physicians and oncology-trained support staff at the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center are trusted partners in returning patients with cancer to good health. Through a combination of expertly delivered, compassionate care and our initiatives to develop new lines of defense against cancer, we offer more than most cancer centers. We deliver the future of cancer care, today.

What type of urinary diversion should I choose?

Each of the three cystectomy and reconstruction options involve reshaping a piece of the small intestine into an internal, bladder-like pouch to hold urine. One end of the new pouch will be connected to the ureters, which are the two tubes that drain urine from the kidneys into the pouch (formerly the bladder). The other end will be handled in one of three ways.

Incontinent diversion

Acceptance after ostomy surgery

Adjusting to life with an ostomy and learning how to maintain it can feel overwhelming. However, it is important to remember ostomies save lives.

The segment of intestine (conduit) ends at the skin level, which is a permanent surgical opening in the belly. Urine will flow from the kidneys through the conduit and into an ostomy bag that’s worn outside the body 24/7 for the rest of your life. You will not be able to control the flow of urine with this option, and you will need to empty the bag regularly to avoid leaks.

This is the most straightforward option with a slightly lower risk of complications. While living with an ostomy is a big lifestyle change, most people master their emptying schedule and can live a full, active lifestyle.

There is a risk of leaking if the ostomy bag is not emptied regularly or if there is not a good seal between the stoma and the bag. There is also a possibility of developing a hernia or infection at the stoma site.

Continent diversion

With this second option, the intestine is folded into a pouch that is connected to the skin by a small channel designed with a one-way valve. You will need to insert a catheter into the stoma every three to four hours to drain the pouch. Some patients prefer this option because they can control their flow of urine and no external ostomy bag is required. However, it is not a common choice in the U.S. due to the risk of pouch stones and infections associated with frequent catheter use and the risk of stoma herniation or infection.

Ileal neobladder

The third option is an ileal neobladder. Rather than connecting to the skin, the intestine is folded into a pouch that is connected directly to the urethra. No ostomy bag is needed, and most patients can learn over time to urinate close to normally during the day by relaxing their pelvic floor muscles and, if necessary, pushing with the abdominal muscles.

You will need to empty the pouch with a catheter for a few weeks to a few months as your body heals. After recovery, you can participate in physical therapy designed to teach men and women how to control their pelvic floor and abdominal muscles to manage urine flow. Up to 15% of patients – and about 30% to 40% of women – may not be able to relax their pelvic floor enough and will need to use catheters long term.

You must empty the bladder every three to four hours to avoid leakage or complications. While most patients learn to manage continence during the day, many will have issues with bladder control while sleeping. The body’s natural internal bladder sphincter (on/off sensor) is removed during cystectomy and cannot be replicated.

Some patients choose to wake up with an alarm every three to four hours at night to urinate. Others wear discreet incontinence garments overnight – some even do so during long days at work to stay dry. Sanders, for example, shared in a news conference reported on by The Athletic that he wears Depend garments while coaching in case he can’t get enough restroom breaks.

Cystectomy is lifesaving, but also life-changing

The brain-bladder connection that tells you it’s time to urinate will no longer work after your original bladder is removed. You will need to empty the new bladder pouch every three to four hours, regardless of which surgery you choose.

Intestinal tissue is designed to absorb liquids, not store them – that is how we digest food. That means the new bladder pouch will absorb urine back into the body if you do not empty it regularly. Absorbing urine can increase the risk of kidney stones and excess acid in the body.

Because the intestines are altered with a cystectomy, you may need to wait a few weeks to resume a normal diet and digestion. The intestinal tissue also produces mucus, which can cause urine blockage as the body eliminates.

Cystectomy can affect sexual function if pelvic tissues and nerves are damaged. Men may not be able to achieve a spontaneous erection after surgery. Pills such as Viagra or Cialis likely will not work if there is nerve damage, but a discreet penile implant or external pump device can be effective.

Women who had reproductive organs removed along with the bladder may enter early menopause and may notice changes in sensation. Hormone replacement therapy and pelvic rehabilitation can help restore comfort and confidence during intimacy.

Choosing the right type of bladder cancer treatment requires open communication with specialists who excel in treating complex cancer and who understand what matters most to you. We are here to provide the information you need to make the best decisions for your cancer care and long-term quality of life.

To talk with an expert about bladder cancer treatment options, make an appointment by calling 214-645-4673 or request an appointment online.